In Part I I discussed the problems facing kids and teenagers in a contemporary culture with easy access to internet pornography. I argued that, as well as being an emerging public health crisis, this can be seen as a visual culture crisis. Tools to deal with the crisis, however, are also to be found within visual culture. This is where relevant, down-to-earth, unabashed and humorous sex education comes in. Sex education that can help children and teens interpret and assess what they see in a critical way, encouraging positive perceptions of body diversity, and sexual diversity. It can help emphasise the importance of ensuring sexual encounters are enjoyable, intimate, fun, safe and loving for both partners at an appropriate age within mutually consenting relationships. It can help children and teens understand that beliefs and emotions surrounding sex are part of a much wider field of interaction; influenced by cultural belief systems, the media, peers, parents and partners.

Not only can good sex education help youngsters deal better with explicit sexual images; research shows that if kids and teenagers are taught well about sex, they tend to delay having sex for the first time, teenage pregnancy rates come down, as do the rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Teaching children and teens about sex is a topic fraught with controversy, and widely polarised opinions often lead to heated debates and a politicisation of the subject matter. Generally on one side of the debate those with conservative views advocate sex education on a need-know basis only, fearing that children and teens will be unduly influenced to have sex, if they are taught about sex. On the other side of the debate, those in favour of early and comprehensive sex education, argue that openness and honesty can assist children and teens in developing a healthy understanding of sexuality, and in turn develop healthy sex lives as adults. Sex education efforts (by parents, schools and institutions) fall into a wide array of variations between the two ends of the spectrum. Until fairly recently the conservative belief-system has reigned, and still does in many places (particularly within faith-based communities, schools and organisations). In some places, such as Scandinavia and the Netherlands a more liberal approach has been developing over the past century, in particular since the 1970s.

Australian Sex Ed

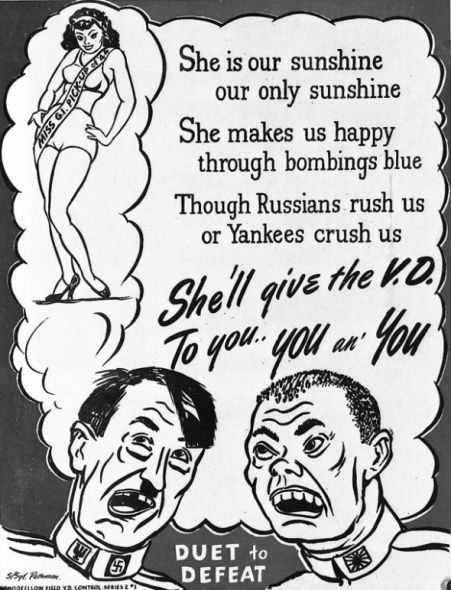

Australia (and most other countries) have had a strained relationship to sex education. The spread of venereal disease amongst soldiers visiting prostitutes during the First and Second World Wars initiated the first large scale sex education efforts in Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom, through mostly misogynistic propaganda posters (see Venereal Disease Propaganda in the Second World War by Joanna Close). Here the ‘loose woman’ was portrayed as the enemy on a mission to spread disease to unsuspecting soldiers.

In the decades following the Second World War sex education in Australia was sporadic and inconsistent. It was taught for example through meetings held by puritan groups such as the Father and Son Welfare Movement, advocating abstinence, and giving moral lectures with very basic anatomical information. Some education for boys took place in schools, but education for girls was very limited.

Throughout the years sex education for both genders has moved into Australian classrooms, though it has been difficult to find a unified approach within the Australian curriculum, and there are still vast differences in the teaching techniques and messages taught to kids across schools. In recent years sexual education has been added to the National Health and Physical Education curriculum in Australian primary and secondary schools. Critics on both sides of the spectrum, however, are unhappy about the changes to the curriculum. Some organisations advocating a more comprehensive and unified approach to sex education are worried that the curriculum is too vague, while other organisations advocating against compulsory sex education in schools argue that the curriculum is too extreme, forcing parents to accept a specific type of teaching that they may not feel comfortable with.

Despite the national curriculum requirements for education regarding human sexuality, it is up to the individual schools to take the initiative to implement some form of sexual education, and laws in some states make it possible for religious schools to legally discriminate against those practicing “unacceptable” sexual behaviour according to the school’s doctrines. As a result there are concerns that sexual education can become irrational, fear-based and stigmatising. For example, one Catholic school ordered students to rip out and destroy a page in their health workbook, which discussed premarital sex and homosexuality.

Generally Australia has seen a shift towards a more conservative approach to politics in recent years. Political alliances with Christian lobby groups has resulted in efforts to stunt the introduction of marriage equality laws, and efforts to sabotage the introduction of the ‘Safe Schools’ program—an anti-bullying initiative, aiming to teach school kids about tolerance towards lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) students (see also Safe Schools Review Findings: Experts Respond).

The recent defunding of Australia’s only youth-led sex education service, YEAH, is an other example of what some describe as an ideological anti-sex education agenda pushed by conservatives. This move comes at a time when sexually transmitted infection (STI) rates are rising amongst young people and condom use is declining. At a time when experts are stressing the need for effective sex education, that promotes safer sex practices, through honest discussions with young people.

What Does Research Say?

Peggy Orenstein from the New York Times writes in her article When did Porn Become Sex Ed:

What if we spoke to kids about sex more instead of less, what if we could normalize it, integrate it into everyday life […]? Because the truth is, the more frankly and fully teachers, parents and doctors talk to young people about sexuality, the more likely kids are both to delay sexual activity and to behave responsibly and ethically when they do engage in it.

Orenstein is echoing the findings of research, which suggests that abstinence based sex education is counterproductive, and may lead to earlier first time sexual intercourse, higher rates of teenage pregnancy, and is likely to lead to higher rates of STIs. A comprehensive study of existing literature compared the age of first time sexual encounters, rates of condom use, rates of STIs amongst youth and teen pregnancies in the United States, Australia, France and the Netherlands. The study reveals that the Netherlands, a country with a comprehensive and “open-minded” approach to sexual education has very low teen pregnancy and STI rates, compared to the United States, where sexual education efforts have been strongly focused on abstinence programs, and where statistics report the highest rates of teen pregnancy and abortions of all industrialised countries (read more here).

Another study that compared female college students in the United States and the Netherlands found that “the American sample experienced sexual behaviours at a younger age and with more partners, whereas the Dutch sample showed a better use of contraceptives during high school, more talk with their parents, and greater sexuality education”. Through in-depth interviews with the young women researchers found the U.S. women felt unprepared for sex, engaged in sex because they were driven by hormones or peers, or wanted to satisfy their partner. They generally had parents who were uncomfortable talking about or silent about sex. The Dutch women, on the other hand, spoke more about being motivated by love, feeling in control of their own body, and about having parents (and teachers/doctors) as supporters and educators, who introduced them to books about sexuality at a young age.

Australia does not generally have an abstinence only approach (though this is promoted in some religious schools); however, it does also not have a comprehensive approach to sex education like the Dutch, or a culture in which sex is readily talked about in a natural and educational way with children and teenagers. Consequently, research is indicating that sex education is starting too late, since children are entering puberty earlier than commonly believed, and since many teenagers are sexually active (see Worried About the Sexualisation of Children? Teach Sex Ed Earlier). Young Australians themselves are reporting that school-based sex education is providing them with important information about sex. They are, however, asking for lessons that focus less on the biological/anatomical aspects of sexuality, and more on gender diversity, violence in relationships, intimacy, sexual pleasure and love. This is what Nelly Thomas calls the ‘sex education paradox’: we live in a culture that is rife with sexual images and content (on the internet, in the media, popular culture, and advertising), but refuses to discuss honestly and courageously the real issues that can either hinder or assist young people in developing healthy, happy sex lives and relationships.

What Can We Learn from the Australian Response to HIV/AIDS Prevention?

What does the history of HIV/AIDS campaigns have to do with contemporary sex education for kids and teenagers? There are obvious ways in which sex education differs from the HIV/AIDS crisis: (1) the emergence of HIV/AIDS was a public health emergency, with people getting very sick, and in many cases dying; (2) the people most affected by HIV/AIDS were adults within particular population groups (in Australia men who have sex with men, sex workers, and intravenous drug users). However, there are also many similarities: (1) the producers of the education materials are dealing with the delicate subject of sex; (2) the materials need to promote safer sexual practices; (3) the materials need to be engaging, informative and memorable.

Australia is widely known for its pragmatic and proactive approach to the HIV/AIDS crisis in the 1980s and 1990s (see for example Learning to Trust: Australian Responses to AIDS by Paul Sendziuk). The key to its success was strongly collaborative partnerships between the government and community organisations. These organisations were mobilised to educate and assist the communities most affected on a grass-roots level, rather than through a top down approach. This meant that educational campaigns could be created that spoke directly to the people within these communities, in a language they could relate to and understand. The key being trust and communication between government authorities, and those working closely with risk groups in peer based organisations (see also Australia’s HIV Response).

In short, the four key elements that made HIV/AIDS campaigns effective were:

- The campaigns were funded by the Government, but developed by peer-based community organisations, who knew well the target audience they were trying to reach.

- The campaigns used straightforward visual language and words that were relevant to the target audience. At times using sexual explicitness, and at times using humour.

- The campaign did not use fear strategies. There is strong evidence that scare tactics generally alienate, rather than engage target audiences.

- The campaign material was incorporated into the everyday lives of the target audiences. For example, ads were run continuously, in weekly magazines published for the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community. Posters were displayed at LGBT clubs, and events.

Despite the obvious differences between sex education for kids and HIV/AIDS campaigns, one could apply parallels between the four key elements:

- Sex education is most effective if done as a collaboration between parents (the primary educators), schools, experienced sex educators, and peer-based programs.

- In an age where many children and teens are exposed to highly sexually explicit material on the internet, using tame and prudish visual language will not seem relevant to kids. To reach kids the education materials must be relevant to the age group, and kids must feel that they can openly ask questions and engage in discussions with the educator. Humour is a good way of making it easier to communicate and engage with kids.

- Fear is not effective in reaching children and teens. Shaming and abstinence only programs will lead to secrecy, and potentially to higher rates of unwanted sex, and/or unprotected sex.

- Incorporating sex education into everyday life is more effective than having ‘THE TALK’ once a child hits puberty. If kids are from an early age encouraged to ask questions, and are given relevant answers, honest communication channels are opened, and kids are more likely to discuss with an adult if they are feeling uncertain, scared or confused. In her resource Talk Soon, Talk Often Jenny Walsh outlines how it is beneficial for parents and schools to keep the conversation open from an early age (listen to Jenny Walsh talk about the subject here). It is also useful for schools to adopt a ‘whole school’ approach, where sex education is not just something the PE teacher does, but something that can be relevant to and incorporated into a wide array of subjects (see for instance the resource Catching on Early).

The Practical Guide to Love Sex and Relationships

From a visual culture perspective then, what does an effective resource for teenagers look like? A good example is a new resource produced by the Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society (ARCSHS), La Trobe University, and funded by the Australian Government. The project was authored by Jenny Walsh, (researcher, educator and curriculum writer within the field of sexual education), Anne Mitchell (researcher within the field of youth sexuality), and Mandy Hudson (community educator). The resources were created on the foundation of Professor Moira Carmody’s Sex and Ethics research and education project, and on the results of the Fifth National Survey of Australian Secondary Students and Sexual Health 2013.

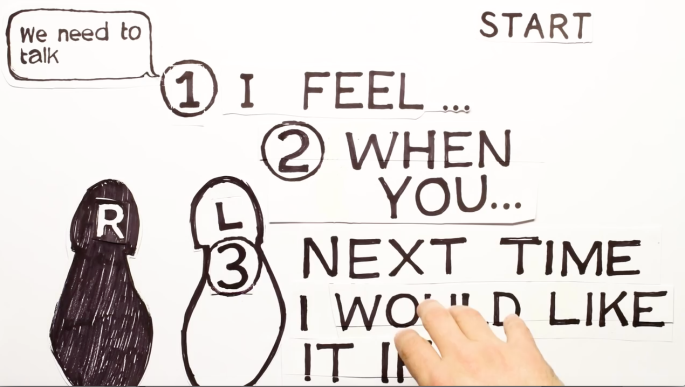

What makes this project stand out is the way it deals with the issues surrounding sexuality and relationships in a contemporary, non-condescending, humorous and appealing way. The visuals are comprised of hand drawn black and white illustrations, with sporadic splashes of colour. The project includes a website with lesson plans, teaching resources, activities and training videos for teachers, and online videos for young people that accompany the lessons. These are divided into age appropriate sections for Years 7 & 8 (12-14 year-olds), and Years 9 & 10 (14-16 year-olds).

One of the strengths of the resource is a series of animations that discuss a variety of topics to do with sex, relationships, gender and pornography. Each is narrated by a young male and female, who have humorous conversations with each other, while drawing the storyline. The actual visualisation of the cutting, pasting, ripping and scrunching of images, continuously changing the context, the emotions and the story, makes the films fresh and funny. In addition, the cut and paste approach also shows the transient, weird and confusing nature of identity, sexuality and relationships. In this way it is not only the message and language that is relevant; the visual style itself becomes meaningful.

In Standing Up For Yourself kids are taught strategies for communicating in a friendship or romantic relationship.

In What to Do if You Like Someone kids are taught strategies for dealing with crushes and rejection.

In Freedom Fighters gender stereotypes are addressed through a humorous sci-fi storyline.

In Porn – What You Should Know the topic of pornography and its shortcomings are discussed in a funny and at times explicit way.

In The Truth About Desire the myths of male and female desire are dispelled.

The Rollercoaster explores the ethics of sexual relationships, and the importance of respecting ones own boundaries and the boundaries of the other person.

When’s the Right Time? discusses the decision making around engaging in first sexual encounters.

The Good Ship ‘Relationship’ deals with relationship issues surrounding trust, communication, respect and breaking up.

The following observations can be made looking at The Practical Guide to Love Sex and Relationships in relation to the above mentioned four key elements:

- Community based rather than top-down: The materials are designed by experts in the field, who have worked extensively as sex educators, and with youth more generally. As with the HIV/AIDS campaigns, this project was designed by those ‘on the ground’, with first hand knowledge and experience working with the community they are trying to reach (in this case teenagers). As part of the project resources have been designed to train and assist the teachers who will be using the material with their students.

- Relevant: The visual language and words used are fresh, funny and relevant to the target audience.

- Non-fear based: Fear or shaming strategies are carefully avoided. Instead there is a strong emphasis on validating diversity in experience, and on safety through honesty and respect. Rather than focus on the mechanics of sex and condom use, the resources focus strongly on the complexity of relationships, emotions, identity and sexual feelings.

- Incorporated into everyday lives: The materials are designed to be used over a period of time, with some used in earlier years of high school and some in the later years. The videos are available online, making it possible for students to revisit them. In this way, the resource can be integrated into the everyday lives of teenagers.

Relevant Sex Education: A Visual Culture Tool

In a culture where sexual imagery is all around us, and where pornography is often the first exposure to sex for many children, experts are emphasising the need for contemporary, honest and relevant sex education. Being taught a more balanced view on sexuality can provide kids and teenagers the opportunity to develop the emotional intelligence necessary to build healthy relationships and navigate a highly sexualised world.

For information to be conveyed in an engaging way it needs to be visual. These visuals need to be cleverly designed to navigate the fragile line between showing what needs to be shown to communicate effectively with kids and teens, while staying within the boundaries of what parents, teachers, politicians, the media, and society at large find acceptable to visualise.

As the controversies over the ‘Safe Schools’ program has highlighted, Australia is still a country with widespread conservative views deeply embedded into its culture. Consequently, it is the job of visual culture makers – graphic designers, illustrators, animators, artists, photographers, and sex educators – to find ways of dealing with the problematics of visualising difficult issues that many would rather not see visualised. If the information becomes too confronting and explicit, there is the risk of political backlash. However, if the material is too tame kids and teens will feel it is irrelevant to their current lived experience; one which is often already saturated with sexual imagery.

The Practical Guide to Love, Sex and Relationships is a good example of a sex education project produced in collaboration between sex educators and visual culture makers, resulting in an intelligent, genuine and comprehensive set of resources. Though some of the resources deal with sex and sexuality, they are seldom sexually graphic. However, when they need to be (i.e. in the Porn – What you Should Know) the illustration style and humour disarms the potentially awkward subject matter. In this way, the creators have found ways of being direct, while remaining within the boundaries of acceptability.

In Part I I suggested that we are in the midst of what might be described as a visual culture crisis—the excessive availability of highly stereotyping sexual imagery (i.e. in popular culture, pornography, and social media). Simultaneously this crisis is an opportunity for visual culture makers to use their craft as a tool to counter the superficiality, stereotyping, and body anxiety this type of imagery can generate. The clever use of visuals, in combination with honest and engaging information, can create deeper and more meaningful ways of understanding sexuality, emotions, relationships and body diversity. This is a call for visual culture makers to take on that challenge.